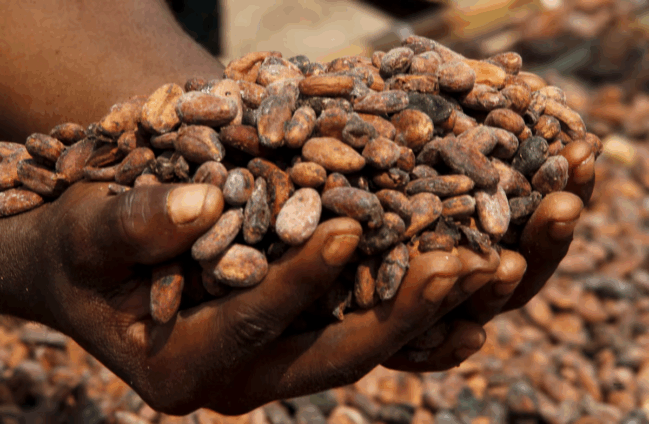

Ghana’s palm oil industry is once again in the national spotlight as the government unveils an ambitious plan to close the gap between domestic production and consumption. Figures from the Ministry of Food and Agriculture’s 2025 report show that the country produces only 50,000 metric tons of palm oil annually, yet consumes five times that amount about 250,000 metric tons. The shortfall is plugged by imports, contributing to a food import bill estimated at US$2 billion each year.

To address this imbalance, government says it will introduce a national palm oil industry policy aimed at reviving local production and developing the entire value chain. The plan includes the provision of 1.5 million oil palm seedlings to farmers, incentives for cultivation, and encouragement for greater participation in out-grower plantation schemes. Officials argue that these measures will strengthen the sector, boost rural employment, and cut the import bill.

Finance Minister Cassiel Ato Forson has already set targets to cultivate 50,000 hectares under the policy, with the first phase expected to attract US$100 million in private investment. From July 2025, new import controls will also take effect, requiring importers to secure permits before bringing palm oil into the country, a move designed to protect domestic producers from the flood of cheaper foreign products.

But recent trends raise doubts about whether the industry can rebound under the current framework. The Oil Palm Development Association reported that Ghana’s palm oil exports plunged by more than 50 percent in 2024, blaming weak government support and the influx of low-cost imports. Farmers and processors warn that unless structural challenges are tackled head-on, new seedlings and incentives may do little to lift production to competitive levels.

One of the sector’s biggest weaknesses lies in its processing infrastructure. While distributing seedlings can increase cultivation, without modern mills, storage facilities, and efficient transport networks, much of the extra yield risks going to waste or being sold off cheaply to middlemen. The fragmented nature of the value chain dominated by smallholders with little coordination also undermines economies of scale and bargaining power.

The new import permit regime, while promising, will be judged on its enforcement. Without transparency and strict oversight, it could open the door to bureaucratic bottlenecks and corruption, discouraging legitimate players. At the same time, Ghana must strike a balance between protecting local producers and avoiding protectionist measures that could inflate prices for consumers.

Beyond production and trade policy, the industry must align with global sustainability standards if it is to secure premium markets. Around the world, palm oil has come under scrutiny for its links to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and poor labor practices. Ghana’s revival strategy must therefore incorporate environmental safeguards and fair labor conditions to compete internationally.

The stakes are high. This policy is more than a push to grow more palm oil, it is a test of the government’s ability to convert political promises into tangible results. If successful, it could transform rural livelihoods, reduce the import bill, and establish Ghana as a credible player in the global palm oil market. If it fails, “Red Gold” will remain a costly missed opportunity, draining foreign exchange while farmers continue to struggle.