The unfolding events surrounding the Ridge Hospital incident are no longer matters of speculation or partisan noise. They are now captured in police briefs, charge sheets, and court writs. These official records demand that we interrogate not merely the actions of individuals, but the institutional responses that have left both justice and credibility in peril.

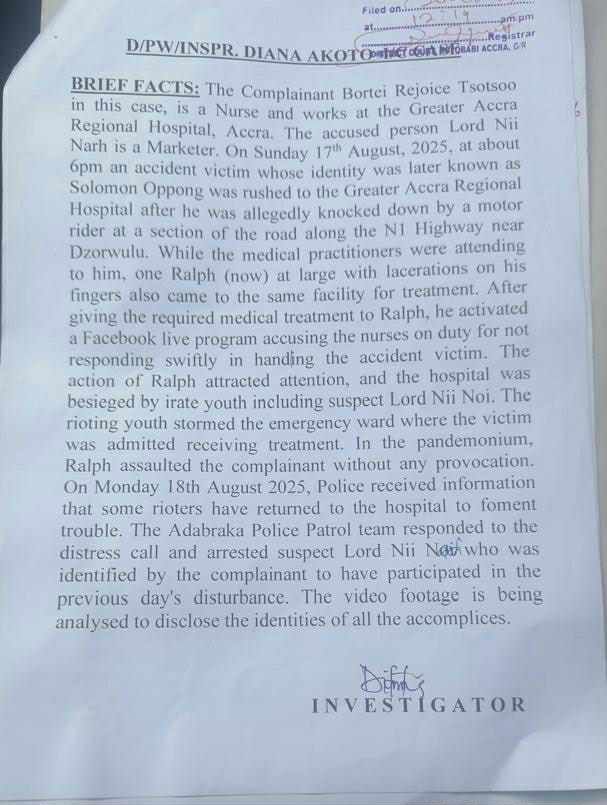

The police fact sheet establishes, as a matter of record, that Ralph Williams, having been treated for minor injuries, proceeded to livestream accusations of neglect against nurses attending to an accident victim. That reckless act precipitated the arrival of an irate mob into the hospital. Within that chaos, the document records that Ralph “assaulted Nurse Rejoice Tsotso Bortei without provocation.” The next day, further disturbances occurred, resulting in the arrest of one Lord Nii Narh, while forty others, including Ralph himself, remain at large.

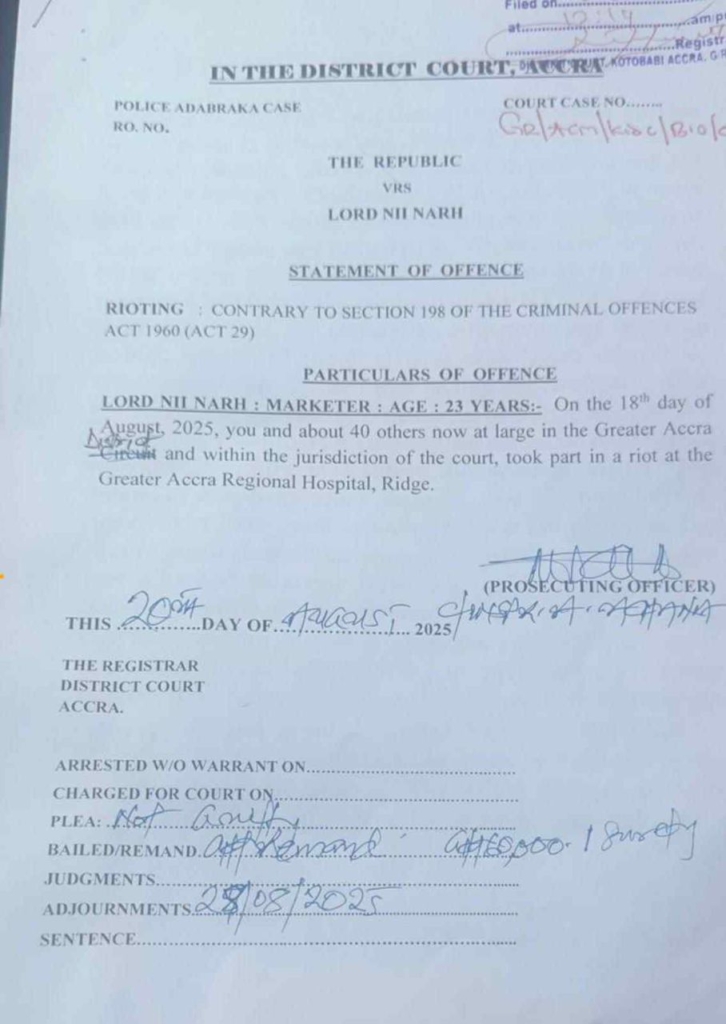

The charge sheet duly styled The Republic v. Lord Nii Narh frames the offence under Section 198 of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29): rioting. The accused has pleaded not guilty, been admitted to bail in the sum of GH₵50,000 with surety, and is to report to the police twice weekly. Yet the police simultaneously acknowledge that a warrant exists for Ralph, who, despite this, continues to grant media interviews. Such contradictions weaken both enforcement and public trust, raising fundamental concerns about the equality of all persons before the law.

Parallel to these proceedings, Nurse Rejoice has invoked her civil remedies. The High Court writ of summons against Ralph represents an assertion of personal accountability. The civil jurisdiction permits her to seek redress independent of the state, and Ralph, once served, has eight days within which to appear or risk default judgment. Here, the complainant has exercised a right of action that is itself a reminder: when state processes falter, private citizens may pursue justice through civil claims.

Yet what has compounded this matter is not simply the conduct of Ralph or his supporters, but the response of the Ghana Registered Nurses and Midwives Association (GRNMA). The Association’s General Secretary, Dr. David Tenkorang Twum, alleged that the nurse had sustained broken bones and dislocations. The investigative committee chaired by Dr. Lawrence Ofori Boadu, however, concluded otherwise: there was no fracture, no dislocation. The police fact sheet confirms the allegation of assault but does not support any claim of such grievous injury. Thus, we are confronted with a dual reality: the fact of assault stands as a live allegation, but the GRNMA’s embellishments lack evidentiary foundation.

Further, the Association’s Public Relations Officer, Sarah Danquah, has claimed possession of a video depicting Ralph slapping a pregnant nurse, while simultaneously admitting that it was not submitted to the police or the investigative committee, but instead earmarked for release to a television station. This posture is untenable. Evidence in a criminal matter is not the property of a union or its officers. It belongs to the judicial process. To withhold such material is to risk obstruction; to release it first to the media is to trivialise justice into spectacle.

The questions that arise are therefore both legal and institutional. Did the supposed pregnant nurse lodge a report with the police? Did hospital authorities ensure that all nurses on duty submitted statements? Why was there silence until it became convenient for media theatrics? These are not mere technicalities. They speak to whether institutions, both professional and governmental, take seriously their obligations to the truth.

The implications are clear. The embellishment of injuries by the GRNMA has compromised its credibility. The hoarding and politicisation of potential evidence undermines confidence in its leadership. The failure of law enforcement to apprehend a man under warrant while he parades on media platforms diminishes respect for the rule of law. And the cumulative effect is that an already fragile health system is subjected to further erosion of public trust.

The path that should have been taken was elementary. Facts must precede rhetoric. Evidence must be handed first to the police. Public statements must be anchored in demonstrable truth. Hospitals must not be turned into bargaining chips. And the professional oath must outweigh any partisan loyalty. Instead, every one of these principles has been sacrificed at the altar of expedience.

The Ridge scandal is thus not merely about Ralph, or Lord Narh, or even Nurse Rejoice. It is about whether institutions entrusted with responsibility, the police, the unions, the courts, will treat justice as process or as performance. At present, the signs are troubling. We are witnessing justice trivialised into entertainment, the courtroom reduced to stagecraft, and truth relegated to a disposable prop.

But justice is not entertainment. Justice is not a Facebook Live. Justice is not a headline to be timed for primetime. Unless this country rediscovers the discipline of facts, evidence, and process, we will continue to bury truth and trust in the same shallow grave.

Footnotes:

1. Police Fact Sheet, Greater Accra Regional Hospital incident, 17–18 August 2025 (Investigator’s Brief).

2. Charge Sheet, The Republic v. Lord Nii Narh, Adabraka District Court, 20 August 2025.

3. High Court Writ of Summons, Rejoice Tsotso Bortei v. Ralph Williams, August 2025.

4. Investigative Committee Report chaired by Dr. Lawrence Ofori-Boadu, concluding no fracture or dislocation.

Note: The complainant nurse, Rejoice Tsotso Bortei, was still hospitalised as at the latest court updates on Thursday. She was discharged on Friday.